The other day, I was looking around YouTube and came across YouTube's new application called "Warp". And, while I'm not sure if it's the same thing as a Mash-up, it's really kind of fun. In fact, it might be more of a visualization.

Warp visualizes the connections between videos. It can only be used in full screen mode and its icon is in the bottom left corner of the screen - it looks kind of like a web map. So, I searched for Cesc Fabregas, Arsenal's up-and-coming Spanish midfielder. I watched the video in full screen mode and then clicked on the icon. Immediately, a bunch of different bubbles splurted out all over the screen. From there I was connected to a number of other bubbles that were related to the first video. I found my way, somehow, to a Puss in Boots video clip from Shrek.

By clicking on a bubble, you can watch the clip. Once the clip is finished, a line appears and connects you back to the original video. It was really a lot of fun to see the wacky connections between videos.

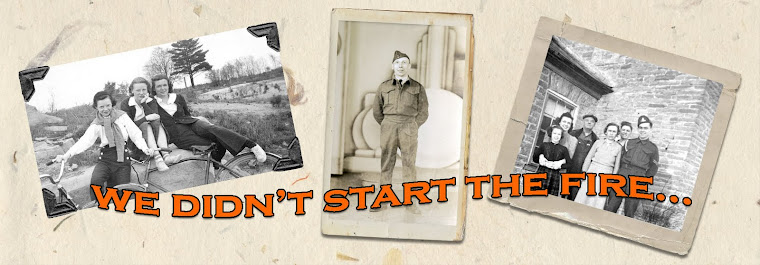

This sort of visualization or application, or whatever it is, would be really cool if it could somehow be used on old, historical (ahhhh...the real connection) photos. If this visualization could somehow be applied to family photos you could roll your mouse over a person in a photo and all of a sudden bubbles would display his/her family and friends and even other photos of the same person. This tool would be great for genealogists.

I'm not sure that it's even feasible to use Warp in such a way that I described above but it's interesting to imagine the possibilities. So, go try it and think of some other neat ways to use Warp!